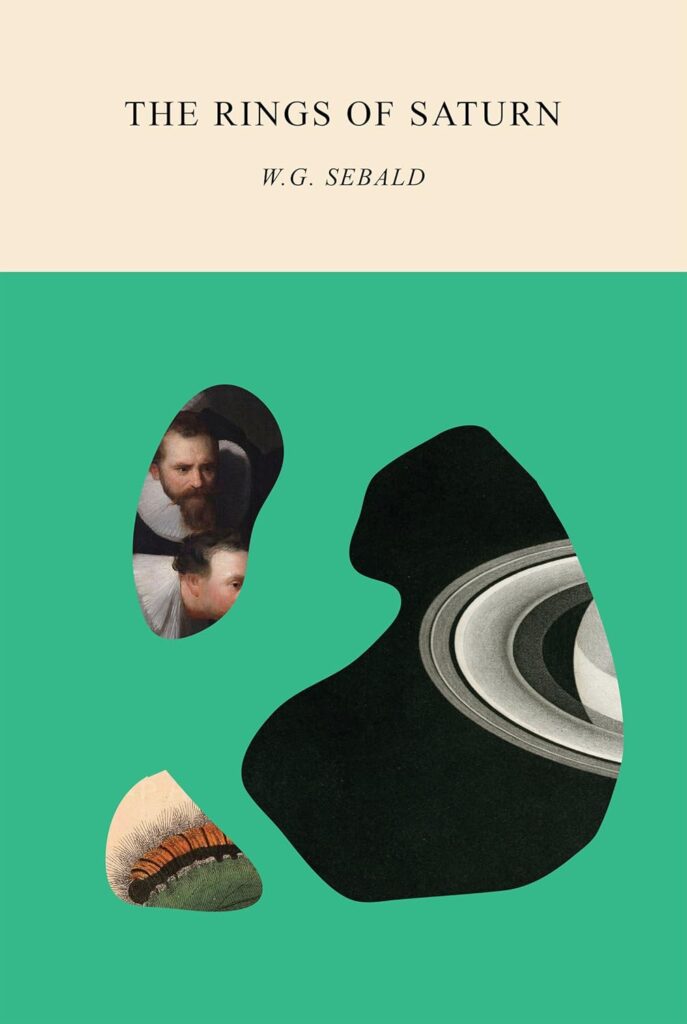

In The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald gives us a book that is neither fiction nor nonfiction, neither travelogue nor essay, and yet each of these genres flickers through it like a faded negative—uncertain, unstable, and all the more haunting for it.

In The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald gives us a book that is neither fiction nor nonfiction, neither travelogue nor essay, and yet each of these genres flickers through it like a faded negative—uncertain, unstable, and all the more haunting for it.

The book defies summary. On the surface, it recounts a solitary walking tour along the Suffolk coast. But this is no memoir in the conventional sense. The narrative quickly strays into meditations on the decline of civilizations, vanished towns, silkworms, Rembrandt, Roger Casement, the horrors of the Belgian Congo, the lost estate of Somerleyton, and the melancholy fates of long-forgotten scholars and eccentrics. It is a walk through memory, through ruin, through the unquiet past buried just beneath the topsoil of modern life.

Sebald’s voice—so quiet it barely rustles the page—has a strange gravitational force, pulling the reader into a slow drift of thought, image, and allusion. Reading him feels akin to watching a decomposing reel of film, where fragments blur and warp until a ghostly new coherence emerges. It is not unlike the cinematic work of Bill Morrison, particularly Decasia, in which decaying nitrate footage becomes a canvas for something both fragile and transcendent. Like Morrison, Sebald understands that deterioration is not the enemy of meaning—it is where meaning hides.

This elusive quality may help explain why The Rings of Saturn has garnered a cult following, while remaining relatively obscure outside literary and academic circles. The book refuses a commercial pitch. There is no tidy plot, no clear resolution. What is it about? A man walks. He remembers. He thinks. He dreams. And yet it inspires fervor. Because the book resists classification, it opens itself to obsession, to acts of imaginative devotion that extend far beyond the printed page.

One of the most compelling examples of this is Barbara Hui’s Litmap project. Hui, a software developer and scholar, created an interactive digital map that tracks every geographical reference in The Rings of Saturn, linking each location to the corresponding passage in the book. Originally part of her UCLA dissertation in comparative literature, Hui’s map allows readers to follow not just Sebald’s literal journey, but the expansive, imaginative one—charting how the narrative slips from Suffolk to China, from South America to the Belgian Congo, all within a single paragraph. The map becomes a visual representation of how Sebald’s mind works, spatializing memory and metaphor in a way no print medium can.

Sebald’s influence extends far beyond the academy. In 2012, director Grant Gee released Patience (After Sebald), an experimental documentary that retraces Sebald’s Suffolk walk while layering interviews, archival footage, and reflective voiceover into a cinematic echo of the book’s associative structure. Artists and writers—from Tacita Dean to Robert Macfarlane—speak not just about Sebald’s work, but about its effect on how they see the world. The film, much like the novel, is not about answers but about resonance.

This resonance has inspired exhibitions as well. Tate Modern’s 2006 Rings of Saturn exhibition invited contemporary artists to create work inspired directly by Sebald’s tone and method. Later, “Waterlog: Journeys Around an Exhibition,” assembled by a consortium of British artists, offered further responses to The Rings of Saturn in a variety of media—sculpture, sound installations, and conceptual poetry, all anchored in the Suffolk landscape. One particularly moving piece by Alec Finlay featured poetry inscribed on lifebuoys, floating symbols of rescue or perhaps loss—apt for a book where the sea is always encroaching.

Some readers go even further, transforming Sebald’s walk into a kind of pilgrimage. Writers, Francisco Cantú being but one of them, have physically retraced the route, encountering in real life the collapsed bridges, shuttered houses, and vast quiet fields that populate Sebald’s pages. These readers don’t just analyze the book; they live it. The boundary between text and world dissolves. This is not a book you finish. It is one you inhabit.

In a passage that captures the unsettling power of Sebald’s vision, he writes:

I was overcome by the almost blinding clarity with which everything was lit up, and at the same time filled with a vague feeling that something was about to go terribly wrong.

Here we find the paradox at the heart of The Rings of Saturn: lucidity and dread coexisting, the world rendered hyper-visible just as it begins to disintegrate. The clarity is painful, the foreboding never fully named. Like a Dostoevskian monologue whispered through layers of gauze, the book moves through a subterranean moral register, excavating the forgotten and the unspoken with a gaze that is gentle, almost apologetic, and yet unrelenting.

And what of its title? The rings of Saturn—composed of dust, ice, and the fragments of shattered moons—are beautiful, but they are also debris. They orbit a planet named for the Roman god of time, wealth, and dissolution. One might see in the title a metaphor for the central preoccupation of the book: that our histories, our empires, our thoughts, all orbit ruin. We are surrounded by the remnants of what once was—objects and lives circling endlessly in the gravitational field of loss. Yet Sebald doesn’t give in to despair. In the quiet persistence of his walk, in the very act of noticing, he offers a kind of redemptive attention.

There are no neat comparisons, but if one must gesture: Sebald’s work evokes the meditative depth of Proust, the historical gravity of Conrad, and the looping dread of Thomas Bernhard. And occasionally, as if by accident, it grazes the spiritual desperation of Dostoevsky—not in fire or brimstone, but in silence, in shadows, in the ghost of a thought not quite expressed.

In the end, The Rings of Saturn is not about what happens. It is about what remains. A thread of thought. A shadow on the beach. A silk cocoon in a cabinet. A man walking alone.

Available At

Leave A Comment