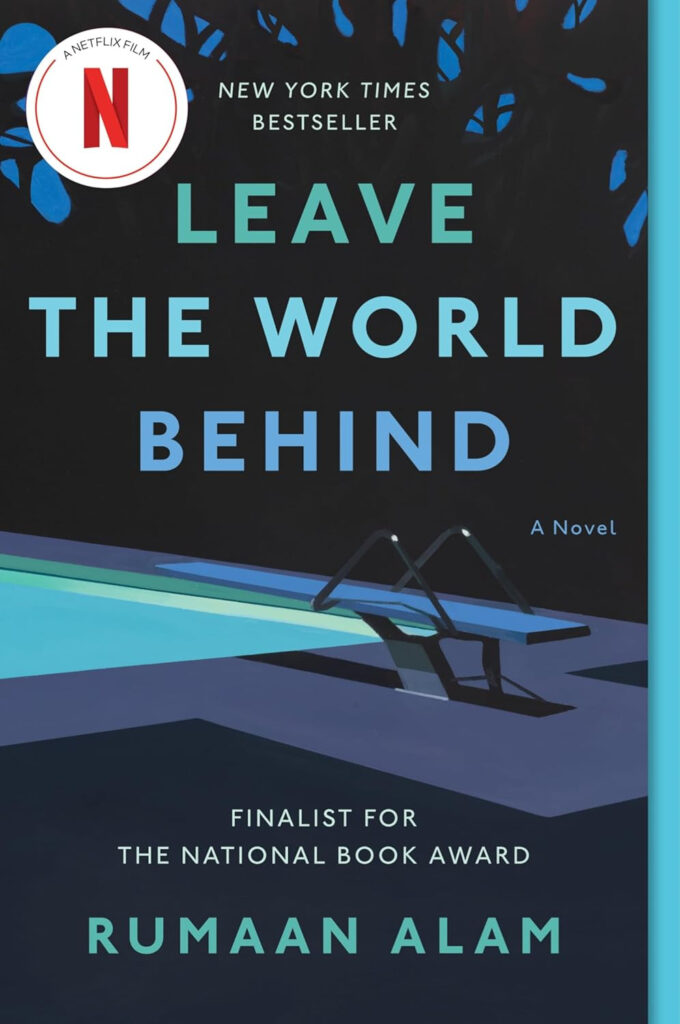

Rumaan Alam’s Leave the World Behind is an apocalypse novel that refuses the spectacle of apocalypse. A Brooklyn family – Amanda, Clay, and their two kids – rent a Long Island house for a week of curated tranquility. Then, late at night, the owners – an older, urbane couple – knock on the door, reporting a massive blackout in the city. From there, the novel tightens like a tourniquet. Power hiccups, phones falter, animals stray into the yard, and the social fabric thins to translucent gauze.

Rumaan Alam’s Leave the World Behind is an apocalypse novel that refuses the spectacle of apocalypse. A Brooklyn family – Amanda, Clay, and their two kids – rent a Long Island house for a week of curated tranquility. Then, late at night, the owners – an older, urbane couple – knock on the door, reporting a massive blackout in the city. From there, the novel tightens like a tourniquet. Power hiccups, phones falter, animals stray into the yard, and the social fabric thins to translucent gauze.

What’s “happening” remains largely offstage, and that’s the point: dread, not data, drives this story. The book was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction, and you can see why – its nerve endings are tuned to our era’s constant hum of threat. Alam’s language is a velvet garrote – elegant, then suddenly constricting. Sentences stroll, then pivot with a predatory snap.

Even the commute seethes: “Roads merged into one another. The traffic congealed. Their gray car was a bell jar.” That’s the book in miniature: society as terrarium, fogging up with breath and fear. The narrator roams omnisciently, confiding little moral asides, taking the temperature of class anxiety and racial awkwardness with a thermometer made of irony. And when the book wants to be blunt, it is. Parenthood, for instance, is distilled to a hard truth: “Worry was infinite.”

Characters are the engine, not the plot. Amanda’s need for control curdles into suspicion; Clay’s vagueness becomes a luxury the moment reality demands competence. The home’s owners, gracious and rattled, aren’t symbols so much as people who have spent a lifetime learning how the world looks at them – and how to look back without blinking. One line from late in the book could serve as its social thesis: “Ruth wanted to say: You don’t need your things. You have us. We have one another.” That plea – so human, so exasperated – signals what’s at stake: not survival kits, but the fragile willingness to recognize each other.

Within its genre, this novel sits in a prickly conversation. If Station Eleven imagines culture as a salve and The Road chases the ember of paternal love through ash, Leave the World Behind traps bourgeois comfort under a microscope and asks whether the specimen is still alive. It shares the domestic dread and satire of White Noise – that static of banality crackling during catastrophe – but Alam updates the frequency for the age of push alerts and curated identities. Older works – say, du Maurier’s “The Birds” or Shute’s On the Beach – often anchor fear in an external, legible calamity. Alam evolves the form by making the calamity illegible and the real disaster interior: the failure of empathy, the comic futility of plans, the moral vertigo of not knowing whom to trust when the Wi-Fi dies.

The prose is also wickedly funny in a way that feels dangerous, like laughing at a eulogy because the absurdity won’t stop tapping your knee. Alam skewers self-image with a surgeon’s wink. A character resolves to do “the right thing,” then the narrative dryly punctures the balloon: “Morality was vanity, in the end.” That’s the book’s bitter merit – nobody, including the narrator, gets off clean.

What sets this novel apart is the precision of its ignorance. Most disaster fiction answers the primal “what happened?” Alam refuses, insisting that anxiety is the protagonist and uncertainty the plot. The result is a tense chamber piece that plays like social comedy until you realize the laugh track is a Geiger counter. And in a handful of sentences, he writes lines that feel already proverbial: “Home was just where you were, in the end.” That’s not optimism; it’s a stripped-down ethic for bad weather.

If you want your end-of-the-world stories tidy, this book will aggravate you. If you prefer them honest, you’ll recognize your reflection in its dark glass. When the lights flicker, the novel suggests, what we have is each other, our uneasy kindness, and our appetite for denial. Or, to borrow one of its slyest epiphanies: “The world was over, so why not dance?”

Leave A Comment