The journalistic phraseology of the title ‘In The Light Of What We Know’ suggests that this will be a novel of discovery where the reader comes to a fuller understanding of the world.

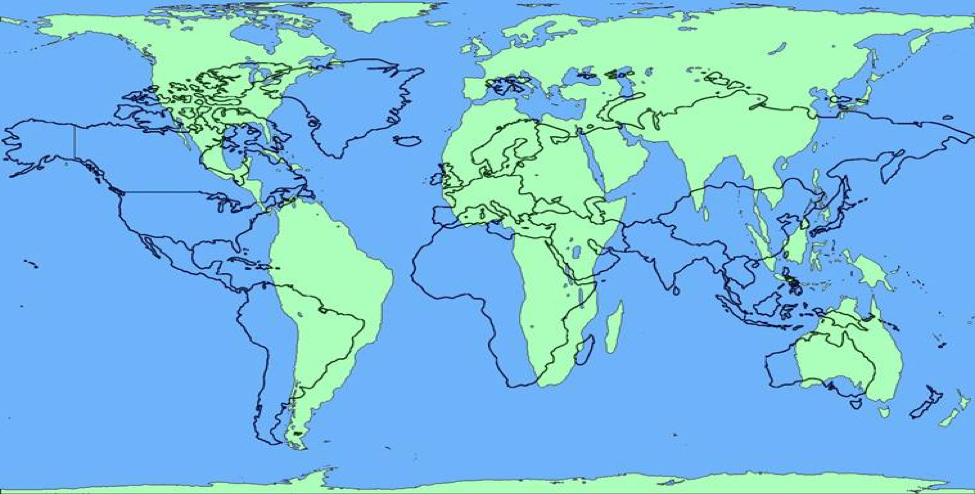

This expectation is undermined in the very first epigram where Rahman quotes W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz and states that history is nothing but a series of ‘pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains’ while ‘truth lies elsewhere […] undiscovered’ (Sebald in Rahman, 2014, pg. 0). This sense that any normal means of orientation will be denied the reader, continues a chapter later when Zafar begins to problematize cartography. He points out that the popular Mercator’s projection of the Earth moves Europe to centre stage and reduces the size of the African and South American continents (see Figure 1 below).

With history and cartography discredited, Rahman moves on to free-will by quoting Saul Smilansky’s Free Will and Illusion on page 28. Indeed, the idea that anything can be learned at all from human action is challenged in the epigram on pg. 115: ‘Sometimes, Tom, we have to do a thing in order to find out the reasons for it. Sometimes our actions are questions, not answers’ (Le Carre in Rahman, pg. 115).

This increase in the apparent meaningless of the epigrams reaches its climax on page 373 when a place-holding text used by printers for testing style is quoted. But Rahman goes yet further by moving us from meaninglessness to falsehood: we are told on pg. 131 that ‘there is a convention that if you don’t know who the author is, you always attribute [a quote] to Churchill’ before peppering the book with falsified Churchill quotations. In this way Rahman uses the structural device of the epigram, normally used to add some sort of authority to an account, to ask questions about how far knowledge – especially Euro centric models of reality – can bring us closer to the truth.

Figure 1. Mercator’s Projection over actual-scale Peter’s Projection

And yet, the novel is undoubtably full of knowledge – mathematics, philosophy, finance, international relations and history – to such an extent that one is reminded of 19th Century novels such as Moby Dick and War and Peace. Even the dynamic between Zafar and the narrator is reminiscent of a Socratic dialogue, with Zafar playing the wizen philosopher to the narrator’s wide-eyed pupil. The use of an epistolary form, with the narrator constructing the story out of journal entries and tape conversations, further adds to a sense of verisimilitude in the novel. But despite ‘what we know’ in this novel, knowledge only ever gets us some of the way towards the truth and is ultimately used to explore the limits of knowing.

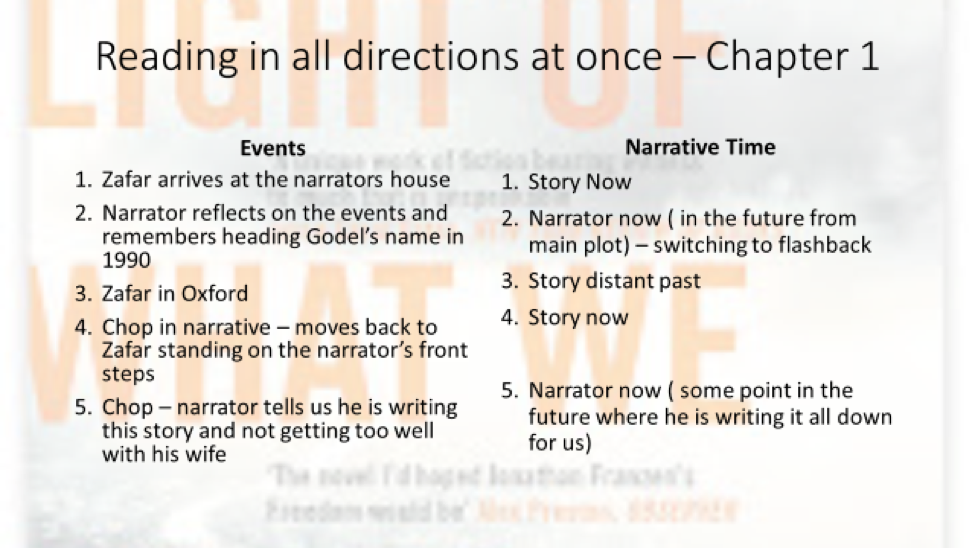

Rahman’s structuring of time is similarly disorienting for the reader. In Chapter 1 the action starts in the story-now with Zafar arriving at the narrator’s home (see Figure 2). Time then moves forward to the narrator’s present where he reflects on the day of Zafar’s arrival before flashing back to a memory of hearing the mathematician Gödel’s name in 1990.

The story then moves to the distant-past and gives an account of Zafar going to University in Oxford. There is then a chop in the narrative before we are moved back to the story-now with Zafar still standing on the narrator’s front steps. At the end of the chapter there is another chop and the action moves back to the narrator’s present where we learn he is constructing this novel at his desk. The reader is thus orientating themselves in three different time periods within eighteen pages. Chapter 2 complicates matters further as the action is moved to Afghanistan in yet a fourth time period.

The reader may here expect a split narrative to develop but chapter 3 does not deliver. Instead we move to Zafar’s distant-past in Bangladesh, move back to the story-now as the narrator’s wife comes home to see Zafar in the kitchen, and ends with switching back to Bangladesh. Thus Rahman, in a similar way to the epigrams, uses time to disorientate rather than orientate the reader. He does, however, create a kind of anchor in his narrative by always returning the story back to the narrator writing at his desk in Kensington. In this way Rahman seems to suggest that although knowledge and time are unreliable, the act of storytelling may help an individual to ordinate themselves.

Figure 2 – Table of time arrangements in Chapter 1

While the narrative strategy is undoubtedly complex, the plot lines of the two main characters are quite straight forward. Zafar’s story is an immigrant story with scorned love and ultimate revenge. The narrator’s story moves from childhood to maturity with his current interaction with Zafar enabling him to move past a middle-age crisis. It would have been possible for Rahman to tell these stories chronologically. His cut and shift approach does, however, allow him to cluster events around theme rather than time. This strategy is apparent at the start of chapter 5 when Zafar describes meeting the Hampton-Wyverns and begins to understand the problems of navigating an English class system in which he does not belong. The question posed here can be summarised as: How far can anyone understand a culture if they are not born into it? A few pages later on, pg. 129, the story moves back to the narrator who introduces us to Gödel’s Incompleteness theorem, which states that imperfect understanding is a mathematical fact of life. The story then moves to the narrator’s near past where he reflects on the 2008 financial crash, which once again illustrates how models of reality will always be flawed. Rahman can be clearly seen to cluster pieces of his narrative around theme and in doing so seems to mimic the processes of the human mind, which takes pieces of experience, personal and shared, and attempts to organise them into some sort of meaningful whole.

This need to make sense from disparate parts is relevant to the immigrant experience that Rahman himself lived. The dust jacket tell us Rahman was born in ‘rural Bangladesh’, was educated in ‘Oxford’, worked as a ‘banker’ on ‘Wall St’ and even practised as a ‘human-rights lawyer’: all biographical details that make their way into the characterisation of Zafar and the narrator. Zafar comes from a ‘mud hut’ infested with ‘rats’ where he went to a school and was ‘beaten black and blue’. He has ‘enough fight’ for any job and fits well into the America ideal of the self-made man.

The narrator on the other hand grew up in ‘Princeton’ as the son of a university professor before going to ‘Oxford’ and working in ‘banking’. Here Rahman seems to be splitting his own story – the immigrant outsider and the naturalised member of the establishment – into Zafar and the narrator respectively. The conversation between the two characters can therefore be read as an attempt by Rahman to reconcile these two versions of himself into one whole. Indeed as the book continues there are moments of confusion about which character is narrating the book and in the end the story is dominated by the voice of Zafar, indicating that the narrator, through telling Zafar’s story, has become more unified with him. The narrator even makes this role of writing explicit and hopes ‘that process can illuminate me to me, a kind of eavesdropping on oneself’ (Rahman, pg. 43). Thus Rahman mirrors the fractured identity of an immigrant in the novel’s form and presents storytelling as a potentially unifying force.

Rahman’s ability to marry content and form is not only apparent in the macro structures of the novel, but also in the micro-level sentence constructions. An excellent of example of this can be seen in Chapter 3: ‘It is as if over time the self has divided in two, a mitosis of the man and his memory, that leaves the boy parting from his infant self, and later the adult from the youth, like the image of human evolution, from primate on all fours, through the savage half man, bent double, to the proud heir to earth, Homo sapiens, who walks tall, each man abandoning his predecessor, each stage only preparation for the next, and in the end childhood left behind, put away’ (Rahman, pg. 87-88). Here the theme of changing immigrant identity can be clearly seen in the image of man moving through the various stages of evolution.

Just like Zafar and the narrator, man is presented as divided in ‘two’ and with each new development he must ‘abando[n] his predecessor’ in order to move to a fully matured whole. And yet a sense of immigrant guilt is still present as ‘childhood [is] left behind’ and the identities sculpted by the abandoned home ‘put away’. The novels sweeping use of time is also evident as the reader is moved from the narrator’s present, back to his childhood, all the way back to the dawning of human evolution, through the various stages of Homo sapiens genesis, before ending back in the present. Similarly the use of embedded clauses, restrained diction, and scientific lexis like ‘mitosis’, ‘evolution’ and ‘predecessor’ create an academic register that mirrors the novel’s interest in knowledge, whilst maintaining the idea that it is not a destination, but rather a never ending process. In this way Rahman manages to incorporate the larger themes of the book into his sentences which then, in the manner of a fractal, build up the overall structure of the novel.

In The Light Of What We Know is inarguably ambitious in terms of structure but it does, as already mentioned, draw strongly from existing models. The dual narrator strategy is taken straight out of Sebald’s Austerlitz and the dynamic between the every-man narrator and the awe-inspiriting protagonist owes much to The Great Gatsby. The manner in which the story becomes dominated by Zafar’s account rather than the narrator is indebted to both Sebald and Fitzgerald’s books. What is more original is using a 19th century view of the novel as a symposium of knowledge in order to discuss the limits of knowledge. This era also comes with a certain amount of colonial baggage, which Rahman seems to reapproriate for use in a post-colonial agenda. Through the portrayal of the Hampton-Wyverns the English class system is critiqued. Initially America is offered as a more egalitarian society with Rahman indulging in a spot of flag waving when Zafar reads the inscription on the base of the statue of liberty in chapter 3:

‘“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give us your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’ (Rahman, pg. 107).

Zafar then goes on to tell us he would ‘die’ for an England like that. Quickly, however, the novel begins to critique the colonial projects of post 9/11 America too. The staff of the international aid agencies in Kabul, Emily Hampton-Wyvern included, spend more time in ‘U.N. bar’ then helping the locals. Crane is portrayed as a child-molesting mercenary who finally meets his punishment in the form of a car-bomb. The book also avoids the othering of Afghans as primitive exotics and instead presents a complex political situation where locals work with, against and without westerners. Zafar himself works for the UN for the sole purpose of getting closer to Emily while also keeping a side-line of subterfuge going for the Pakistani secret service.

But it is here that the novel begins to run into trouble, for once the reader is invited to critique and criticise systems of power everything is open to such analysis – including the obvious biographical elements of the novel. Rahman is clearly angry with the systems of Western Capitalism and the injustices he feels have been done to both him and his homeland. And yet Rahman – graduate of four Ivy League Universities, lawyer, banker and published writer – has clearly benefited from this system. Indeed Zafar’s implied rape of Emily, for crimes as serious as repeated lateness and romantic ambivalence, would be read by even the most moderate feminist as misogynistic.

As a male of privilege, Rahman could not have been unaware of his own position as he started forth on a post-colonial critique and perhaps that is why the novel never offers a clear antagonist or call for action. No doubt the old argument about art being above propaganda could be offered in Rahman’s defence here, but such aloofness is surely easier to maintain from the pent-houses of New York and London than in the slums of Bangladesh.

Rahman finishes the book in a completely apolitical manner opting instead for a pseudo-religious appeal to the importance of faith. The narrator believes that Zafar has ultimately failed to ‘take root’ in a new home and must continue to ‘question life’ with no possibility of ever really getting ‘an answer’ (Rahman, pg. 553). Instead he must have ‘faith’ and submit himself to the ‘river’ of life without knowing if it will ‘end in the sea.’ The novel ends by suggesting that we all ‘must accept our place as servants of life’. In keeping with the overreaching theme of the novel the reader is offered no clear answers.

There is also no climactic plot point – Zafar simply leaves the house and the narrator remains to write the novel – in this way Rahman manages to keep those questions flowing in the reader’s mind. So Rahman can be seen to once again successfully marry form to content right up to the end. How far such aesthetic disavowal of political judgement can be truly married to a post-colonial agenda, however, remains to be seen.

Essay by Brian Kelly

https://www.facebook.com/VerbalDischarge1/

Bibliography

Fitzgerald, F. Scott., 2004. The Great Gatsby. New York: Scribner.

Rahman, Z.H., 2014. In the Light of What We Know: A Novel. Macmillan.

Sebald, S. W., 2001. Austerlitz. Translated by Anthea Bell. New York: Random House.

Wood, James, 2014. ‘The World as We Know It’, The New Yorker. Issue: May 19, 2014.

Available At

Leave A Comment